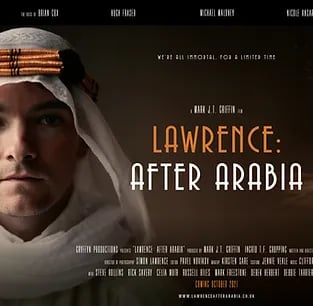

Lawrence: After Arabia. Film review

LAWRENCE OF ARABIADORSET, ENGLANDREVIEWS

11/25/20234 min read

I was so excited when I first heard about the production of a new Lawrence of Arabia film, made on location in Dorset. The premiere was slated to fit nicely with my spring holidays, and I vowed to turn up for it. That was spring of 2020, by the way. So it’s perhaps somewhat ironic that only now in 2023, when resting from only my second bout of coronavirus, that I finally got around to watching the film online.

I hadn’t done any background research on the film before I watched it, so I was expecting a biopic of Lawrence’s post-WWI life. Nothing could be further from the actuality. Not to give away too many spoilers, but it’s based on the argument that that Lawrence did not die accidentally, but was assassinated by the British Secret Service because war was looming and he was seen as a loose cannon on the international stage. I’m not prone to conspiracy theories, but I was willing to suspend my disbelief for the sake of a good story.

Reviews on IMDb vary wildly, and I feel like I have to take a deep breath before giving my own. But you have to begin by remembering that this is an independent art-house film, not a “regular” one, and in places is more theatrical than cinematic. I agree that parts of it are uneven. There are too many brooding shots in my opinion, the script occasionally falls flat, and not all of the actors are on top form (though the director did get cameos and a voiceover from a few well-known names). In my mind, it prompted a comparison with Lawrence’s sprawling, genre-defying masterpiece Seven Pillars of Wisdom, though I don’t know if the director, Mark Griffiths, intended that.

The story is told clearly, and it’s worth telling. Despite my preference for the Occam’s razor version of events, there are some odd circumstances surrounding Lawrence’s death. The hasty inquest and funeral were on the same day, and only a couple of days after his death. No time was given for his close family, travelling abroad, to attend. The one man, a corporal, who claimed he saw a black car at the scene, quickly ended up being moved to Cairo; he maintained his version of the story until… well, that’s in the film so I won’t give it away. Coincidences, perhaps, but tantalising facts, and fair hooks on which to hang a story.

I very much enjoyed drinking in the actual locations, including Lawrence’s cottage, Clouds Hill, and being introduced to the plethora of major historical figures who were friends – and enemies – of Lawrence: Winston and Clementine Churchill, Lady Nancy Astor, and Florence Hardy, widow of Thomas Hardy, to name but a few. Inevitably, the actor who plays Lawrence is considerably better-looking than the man himself, but he plays the part well. Actually, the character with the most drive is the man charge of arranging Lawrence’s assassination (interestingly he is given the name Tyrell – the same as the alleged murderer of the Princes in the Tower!).

Returning to the scenery, there is a minor historical inaccuracy in that the funeral service is re-enacted at the original location, St Nicholas Church, Moreton, and of course you get good shots of the beautiful etched glass windows, which were actually not placed until after Lawrence’s death. But Griffiths could not help that, I suppose.

The film has been criticised for using ‘amateur’, stylised backgrounds in its flashbacks to Lawrence’s desert years, but I saw them more as dream sequences, and actually, the director’s bold solution for not having a location budget, instead of pretending that the sand dunes on Studland beach could double as middle eastern deserts! Talking of which, the discussion of tensions and wrangling over the Middle East and Zionism has particular resonance now in 2023, and is timely reminder of some of the reasons for ongoing conflicts.

Why do I think it has merits? Well, for a start, as an Indie author myself, I admire Mark Griffith’s drive. He had a dream, a story, a plan, and he made it a reality. Like many of us, he has been captured by the enigmatic figure of Lawrence of Arabia, and this was a life’s project. When he couldn’t get a major company to accept the script, he saved and raised the money for the film himself and completed it with a minimal cast and crew. Several Dorset local dramatic groups were included as cast, extras and crew. Keeping it local is not just a homage to the county where Lawrence found refuge; if there is truth to the premise of the story, Dorset may (as Griffiths states in his blog) be one of the first places where the British public was exposed to institutionalised lying via the mass media. Finally, the film has garnered numerous nominations and awards, which I think is a fair recognition of what Griffiths has achieved. Despite its flaws, it certainly kept me awake thinking about what I’d seen.

If you’re interested in Dorset and/or Lawrence, you may enjoy this film, but don’t go into it expecting perfection, or the ordinary. After all, Lawrence himself was neither.

The website for the film, lawrencethemovie.com, has links to sites where you can access the film, as well as the director’s blog I mentioned.